Srinagar, May 13 – The Pir Panjal mountain range, an awe-inspiring stretch of the Middle Himalayas, serves not just as a geographical marvel but also as a natural divider between two distinct cultural and climatic regions of Jammu and Kashmir: the Jammu plains and the lush Kashmir Valley.

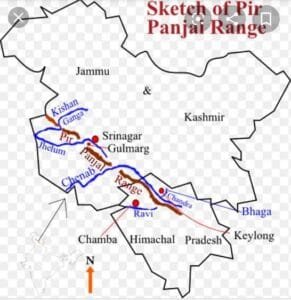

Stretching across the western Himalayas, the Pir Panjal range extends from eastern Pakistan through Jammu and Kashmir and into Himachal Pradesh. In the context of the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir, it forms a vital and formidable barrier separating the southern district of Jammu from the elevated and verdant bowl of the Kashmir Valley.

The range, known for its thick forests, high-altitude meadows, and snow-covered peaks, runs in a southeast-northwest direction. It includes notable peaks like Tatakooti, which rises to over 15,000 feet. These mountains are not merely scenic; they have been historically significant in shaping human movement, settlement patterns, and even political boundaries.

The division created by the Pir Panjal range is more than physical—it reflects contrasting climatic conditions and cultural characteristics. While Jammu experiences a subtropical climate, often marked by scorching summers and mild winters, the Kashmir Valley nestled to the north of Pir Panjal enjoys a temperate climate, with cold winters and relatively mild summers. The Valley is known for its picturesque landscapes, saffron fields, and apple orchards, while Jammu is famous for its temples and a more arid, rugged terrain.

Until the construction of the Mughal Road and the Banihal-Qazigund railway tunnel, the range posed a significant barrier to connectivity. For centuries, people relied on arduous treks over mountain passes like the Pir Ki Gali to move between the regions. The Mughal emperors, notably Akbar and Jahangir, frequently used this route during their campaigns into Kashmir. Remnants of their journeys—caravanserais and Mughal-style arches—still dot the old Mughal Road.

Today, the Pir Panjal is pierced by modern engineering marvels like the Banihal Tunnel and the Chenani-Nashri Tunnel (renamed Syama Prasad Mookerjee Tunnel), which have drastically improved year-round access between Jammu and Kashmir. Yet, despite these developments, the mountains continue to play a profound role in defining identity and governance in the region.

During the winter months, heavy snowfall along the Pir Panjal often cuts off the Kashmir Valley from the rest of India. This seasonal isolation has historically contributed to Kashmir’s distinct socio-political atmosphere. Even during peacetime, weather-induced disruptions along the highway underscore the range’s enduring significance.

Moreover, the Pir Panjal foothills are home to diverse communities, including Gujjars and Bakarwals, who have traditionally migrated with their livestock across the range in search of pastures. Their nomadic routes reflect ancient patterns of coexistence with the terrain, further emphasizing the cultural richness embedded in this natural divide.

The Pir Panjal, thus, is more than a range of rocks and snow. It is a living frontier, shaping the lives, landscapes, and linkages between Jammu and the Kashmir Valley. In times of peace and in times of political tension, its towering presence reminds the people of the region of the majestic but often challenging balance between nature and human movement.